This post on Iglea is adapted and condensed from my book, King Alfred: A Man on the Move, available through Amazon and bookshops.

The Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us that one day after Alfred’s troops came together at Egbert’s Stone, they went to a place called Iglea, a place that is referred to in the Latin of Asser (companion and “biographer” of King Alfred) as Æcglea. Unfortunately, we do not know with certainty the location of this place.

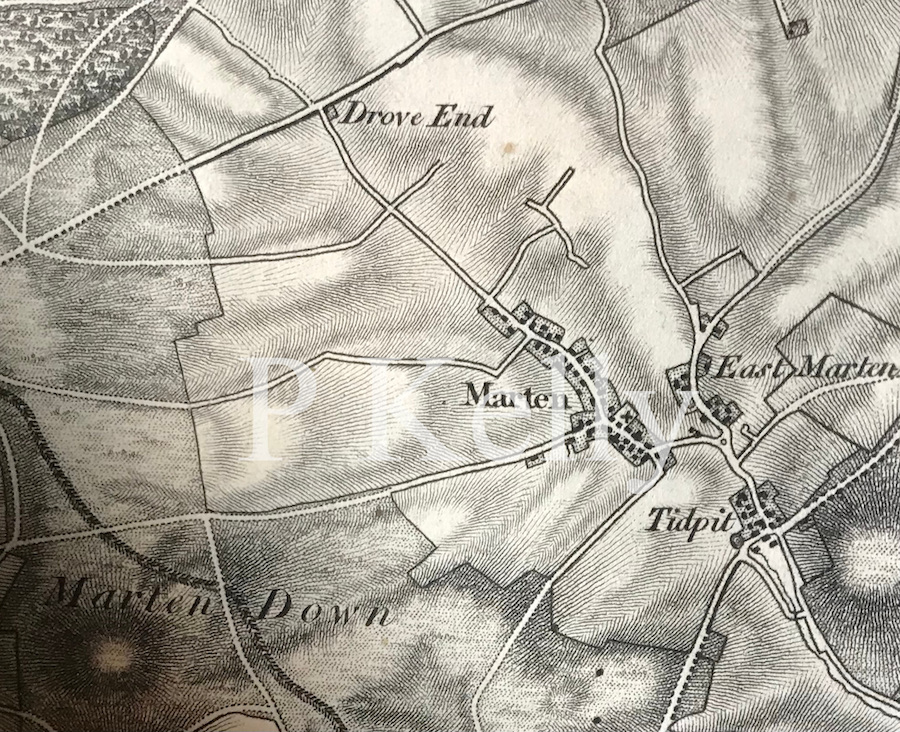

Æcglea was Alfred’s final stop before the Battle of Ethandun, which took place in Wiltshire at Edington or, less likely in my opinion, at the location of the Iron Age hillfort called Bratton Camp. In another post I explained that the most probable location for Egbert’s Stone (King Alfred’s previous stop) was the Upper Deverills, and it seems to me that after leaving there he would have had two main routes to get to the battle site. One would be to follow the Ridgeway to skirt around the north-west of Salisbury Plain in order to reach Bratton Down or to continue on to Edington. The other option being to go straight across Salisbury Plain instead of around it. It seems likely that the location of the encampment at Iglea would depend on which route was taken. Alfred had lost Wessex and was operating in enemy territory and it therefore seems likely that he would have gone across Salisbury Plain rather than around it in order to avoid as many significant settlements as possible, and this is what I focus on in this post. In the video below I refer to Edington being close to Sutton Veny. It is indeed not far, but it is on the other side of Salisbury Plain.

Iglea is similar phonetically to “Iley” and there was an ancient meeting place called Iley Oak in what is today known as Southleigh Wood, previously called Sowley Wood, to the south-west of Sutton Veny. The precise location of Iley Oak in this area may have been where five roads and paths used to meet at a point where today the access to a farm comes off the road connecting Longbridge Deverill to Sutton Veny at the southern edge of Southleigh Wood. I find it striking, and perhaps relevant, that there are the remains of a henge very close to this location. The henge is on private land and is not easy to see. Please be careful if you try to view it from the very fast (nearly) adjacent road.

Although they date to the Late Neolithic, it is possible that some henges, or the places at which they were located, might have retained a societal significance beyond that period, perhaps even through Anglo-Saxon times. In the absence of other evidence, I favour the site of this henge as the site of Iglea/Æcglea.

Southleigh Wood provides one more tempting possibility, which is to be found immediately north of the location described above. I refer to Robin Hood’s Bower. I am aware that this has been put forward by others as the site of Iglea/Aecglea but, for me, it does not outweigh the location of the henge. This is a small ancient enclosure that, like the henge referred to above, would have been present long before the time of King Alfred. The outline of the enclosure is clearly discernible and it has been enigmatically planted with many monkey-puzzle trees.

It has also been suggested that Iglea was at nearby Bishopstrow. The argument that Iley Oak was located here seems to be tied up with an idea that Iglea would probably have been an island (with the Ig part of the word Iglea meaning island) in the River Wylye. There is an island in the Wylye as it flows past Bishopstrow at Boreham Mill and the road that leads north out of Bishopstrow goes right across the middle of it (look out for the two bridges). However, it seems that we cannot prove that there was an island there in Alfred’s time (it could be the result of later human alteration to the watercourse). All in all, I did not find the arguments for this location to be strong enough to outweigh those that can be applied to the location near the henge at the south edge of Southleigh Wood. I did, however, find the argument that Ig indicates an island sufficiently plausible to make this my second favourite. Bishopstrow could also be relevant as a place where legend has it that the staff of St Aldhelm had grown into an ash tree. St Aldhelm’s church at Bishopstrow is 14th century, but it could have been built over an earlier Saxon church. It is therefore possible, had he been close by, that the pious Alfred could have prayed here before the final march to the battle at Ethandun.

There is another (in my opinion, less likely) candidate for Iglea where an unusual number of paths met to the south of Sutton Veny. This, along with possibilities relating to King Alfred going across Salisbury Plain instead of across it, will have to wait for a later post.

There is much more about the travels of King Alfred in my book, including maps and references. Tap or click the image of the front cover below.