The following article on King Alfred and Wimborne is adapted from, and provides additional materials for, my book, King Alfred: A Man on the Move, available from Amazon It would be great if you could support this project by purchasing a copy.

Death of Æthelred

Wimborne (or Wimborne Minster) is a significant historic town in Dorset and is the location of the important Wimborne Minster, which has a history going back to the 8th century. Most versions of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tell us that after the 871 AD battle at Meretun (unknown location, but possibly Martin in Hampshire) King Æthelred, Alfred’s older brother, was buried at Wimborne. However, one version of the Anglo-Saxon Chronicles tells us that he was buried at Sherborne, which seems plausible as the two previous kings and brothers of Alfred, Æthelbald and Æthelbehrt, had been buried there. I consider it possible that Æthelred was initially interred at Wimborne, and then later moved to Sherborne, probably because of the relative importance of the latter location. It is further recorded that Alfred had been present at his brother’s funeral rites, which is what we would expect.

Alfred becomes King

We know that Alfred himself became king after the death of King Æthelred, although the location where this formally took place has not been recorded. I suggest, however, that there is a good chance that Alfred became king at Wimborne, particularly if he had already been designated as next in line, which Asser tells us was the case. Alfred’s immediate elevation on the death of his brother also makes sense in the context of the kingship having run sequentially through Æthelwulf’s sons up to that point. Asser points out a couple of times that Alfred had been what he calls secundarius and that he took over immediately (confestim) on the death of his brother. It should be borne in mind, however, that just because we are told that Æthelred had been buried at Wimborne does not mean that he died there, with this meaning that Alfred could have become king somewhere else. Nonetheless, Wimborne seems plausible because we know that it had significance because the royal estate there was seized in 899 by Æthelwold after Alfred’s death (if it was significant in 899 it seems likely that had been so in 871).

The battles that took place in 871 indicate that Wessex was clearly in a state of emergency at the time King Æthelred died, and perhaps the formal ceremonial arrangements of Alfred’s accession were delayed until the relatively peaceful period between 872 and 874 when the Vikings that had been at Reading were causing trouble in Mercia and Northumbria instead. If there was ever a formal ceremony, we have no evidence of it. It has been suggested that Alfred became king in Winchester, but I have seen no evidence of this. Furthermore, it appears that Kingston-upon-Thames had not yet become (as it would) the favoured site for the consecration of the Anglo-Saxon kings.

The relationship between King Alfred and Wimborne is an interesting one.

There is much more about the travels of King Alfred in my book, including maps and references. Tap or click the image to learn more.

Update on the plaque in Wimborne Minster.

I came across some articles of the Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club, which shed further light on the plaque (or, more correctly, plaques. The 1918 contribution by Reverend Almack reminds us that restoration took place 1855-7. he goes on to tell us that the slab that had been over the remains of King Æthelred “was cut away, in spite of protest, and only the portion sufficient to cover the brass was allowed to remain.” We are also told that during restoration the remains of a tesselated pavement and the bases of columns were observed, which has led to speculation that the first church here was built over a Roman temple. However, the authors of the Royal Commission on Historic Monuments suggests that this may have been from the original church of St Cuthburh.

This monument was clearly a hot topic as in the 1919 issue there is a long article by Reverend Fletcher, which he had read out in 1918. In this he states that the plaque(s) were “placed in the floor on the north side of the sanctuary at Wimborne Minster, about 15 ft from the east wall, and consists of three metal plates.” Of course, today, the plaques are on the wall and not on the floor. The author reminds us that brasses were not used in England until about the 13th century, although this one may be more recent, possibly 15th century. Therefore, the brass cannot be contemporaneous with the death of Æthelred. Furthermore, the author points out that the section with script is even more recent and is copper not brass. This second inscription plate was found to be a palimpsest and may be 18th century (Dorset Natural History and Antiquarian Field Club Proceedings 1919, p32)

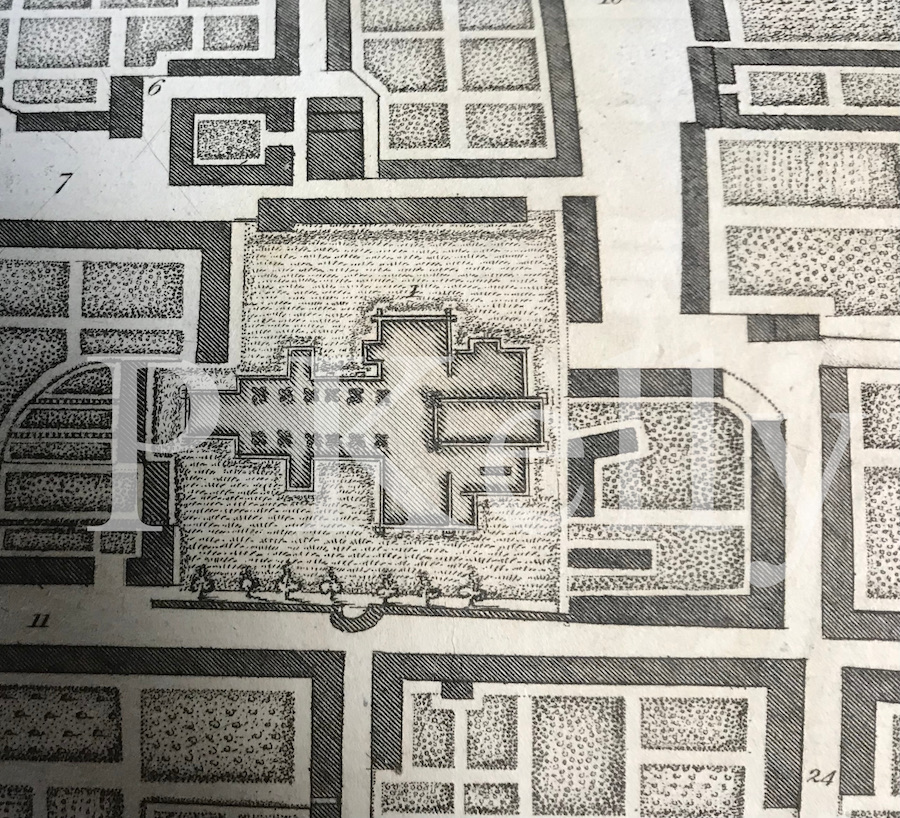

So, where are King Æthelred’s remains? Unless there is a huge coincidence, we can be sure that they are not where the plaque is, because it has been moved at least once, and is not contemporaneous with his death in any case. It is possible, however, that when the brass sections were made they were placed at the (at least claimed) location of his remains, which would have been within the footprint of the Saxon church and probably near the altar. This would have been just to the east of the crossing, which seems to have stayed in the same place over time (RCHM. Dorset. Vol V; East). It needs to be recalled, however, that he may have been moved to Sherborne. If he had been moved to Sherborne, there was still a record of him by Leland in 1536 at Wimborne.

Leland describes the text on the plaque, which is the same as we have now except for a different (and obviously wrong) date. Camden, writing in 1586, tells us that the tomb had been recently repaired, so it is possible that the date was corrected then and that the text part of the plaque that we have now dates to that time. Or perhaps Camden just wrote the wrong date down and the plaque did not need correction at the time of the repair. Leland also tells us that by 1828 Æthelred’s tomb had been by that of St Cuthberga, which was at the north side of the Presbytery (chancel). He goes on to tell us that St Cuthberga was then moved to the east end of the altar. St Cuthberga is hugely important to this church, but I will have to go into that further elsewhere, time permitting.

Things are further complicated by the finding (as reported by a Dr Smart in The Genetleman’s Magazine, 1865) that when enlarging a vault under the presbytery in 1837, a skeleton of a man was exhumed at the north east corner, near the site of the original altar. This man was 6ft 4 ins tall. Could this have been Æthelred? It certainly seems a suitable location. This same source includes a suggestion that Æthelred died of his wounds at Witchampton (north of Wimborne), based on this being a similar name to “Whittingham”, a place mentioned by earlier writers, such as Camden. However, we don’t know where Camden got this from and, in any case, Witchampton does not seem to connect with the name Whittingham (Mills, Place Names of Dorset. Part 2). Witchampton as a legendary place of death of Æthelred is again mentioned in A Topography of Alfred’s Wars in Wessex, by Williams-Freeman. However, I haven’t come across anything to support this other than that Witchampton is on a plausible route between Martin and Wimborne. Nonetheless, a portable information board in the church at Witchampton states: “The old records say his funeral procession came through Witchampton, where the bier rested on its way to Wimborne. Among the mourners was his brother who later became King Alfred the Great.” Unfortunately, we are again not told what these “old records” are. Witchampton was also the location of the discovery of late Saxon chess pieces.

A King Sigferth was also buried at Wimborne, in AD 962. This is a mysterious character who we know very little about, including what he was king of. The entry in the Anglo Saxon Chronicles is generally translated that he committed suicide. I am uncertain whether he would have been allowed to have been buried in the church if that was the case. Much rests on the meaning of offeoll in “Sigferð cyning hine offeoll“.

It is fascinating to think that Wimborne Minster once had a spire, which fell in 1600.